About 6 months ago I got an email from Will – a fellow participant in the Bob Marshall Wilderness Open and one who was faster than I in 2018. Clearly a man who likes to suffer, he wondered if I wanted to do a trip British Columbia’s Caribou Mountains.

The Caribou’s form the northern tip of the Columbia Mountains, which are adjacent to and often confused with the Rockies. Of the ranges shown below, the Caribou’s in the top left are the least visited owning to their northern location, thickest brush (from being on the wetter west side and further north), and lack of national parks and other publicity. It’s an area so wild that what may be the largest cave in Canada with a gaping 100m wide mouth visible in Google Earth was only discovered last year by a helicopter crew. Hence moreso than the other ranges, the Caribou’s still have unclimbed peaks, unpaddled rivers and almost no trails – a situation Will wanted to investigate.

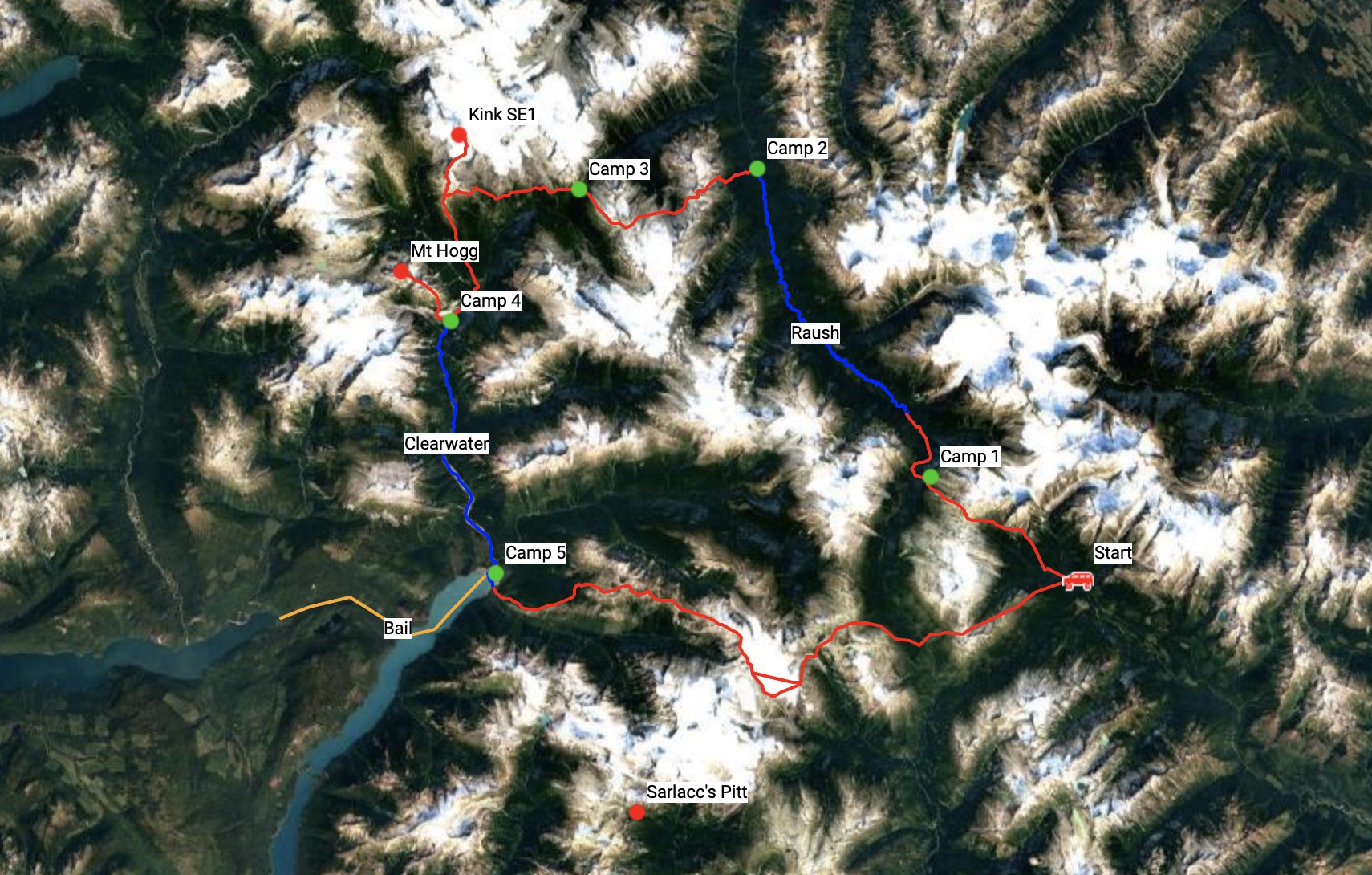

Will proposed a hike/raft loop containing two rivers and up to 3 unclimbed summits. The rivers were the Raush and the Clearwater. The Raush flows north and has been paddled in years past by two prior parties but only by helicopter access – leaving the first human powered descent up for grabs. The upper Clearwater has seen no recorded paddling at all.

The trouble with such a trip is connecting these rivers, because the land doesn’t contain a single step of man made trail. Sticking to the alpine is the preferred way to go, but this landscape isn’t particularly conducive to that and thus we wound up with a route containing 40km (25 miles) of water and 90km (55 miles) on foot – of which about half was pure bushwacking and often on steep sidehills. That route plan is shown below, with a start in the bottom right corner.

Day One (7 Miles)

On July 6 we woke in my car parked at the end of the North Thompson FSR and began the process of turning lines on a map into experiences. Our immediate objective was to get to the Raush River 17 km (11 mi) away. It sounds like a short day, but it would take us nearly two. After two hours were we hardly a mile from the car. Thick brush (mostly Rocky Mountain Rhododendron but with good showing by Devil’s club, green alder and willow) combined with steep sidehills meant tedious progress as we worked our way up the headwaters of the North Thompson River.

We thrashed alongside the river for a few hours before concluding it wasn’t working. Thick brush is hard, but sidehilling through thick brush is at another level entirely. We modified the route away from the river and straight uphill to reach the alpine sooner – albeit further from our pass. It was a steeper line but a straight ascent was better than sidehilling. Even still, it was early afternoon before we completed the 3 miles to the alpine where the landscape opened.

The alpine was awesome – as it always is – and we were able to pick up the pace over the pass into the Raush drainage. We contoured through alpine towards the Raush River to minimize miles below treeline. By 6 pm were were in a beautiful alpine bowl that was likely the last good camping for a long time, so we called it a day after 7 miles and left the remaining 4 for the morning.

Day Two (4 Miles Hiking, 13 Miles Paddling)

I was hoping we’d make it to the Raush River on day one because 11 miles simply isn’t that far, but bushwacking is nothing like hiking on trail so I wasn’t entirely surprised we were starting day 2 with a lengthy section of bush remaining. Not far from camp descended below treeline where the tedious sidehilling bushwacking resumed.

Will and I had talked a fair bit about safety on this trip, and it became clear that our present affliction of wiping out every 5 minutes in the thick, wet vegetation wasn’t sustainable from a safety perspective. You can slip and wipe out on wet roots and shrubs 5 or 10 times and be fine, but if you’re going to wipe out 100 times per day for an entire week, there’s a pretty high chance one of those times will be a bad one. Regular wipe outs were unavoidable but we still wanted to reduce that to 10 or 20 per day instead of a 100. To help us stay vigilant, we started playing a game were you gained a point for each wipe out and the first one to 5 or 10 points got a penalty, like having to start the fire that night. We played many rounds that day.

By noon we were done with the sidehilling and had mostly a straight shot to the river in thankfully more open forest. For the first time we made observable progress below treeline. We passed below a waterfall in the Upper Raush and even found a game trail along the river (our first of the trip).

We arrived at our put in on the Raush in late afternoon and set about inflating our rafts, which was when I noticed that my paddle shafts were missing. I have (had?) a 4 piece paddle with two blades and two shaft pieces, and apparently the two shaft portions had been ejected during one of my numerous wipe outs. Finding them was hopeless, so Will and I discussed our options included him towing me, hand paddling, or constructing some sort of a shaft from nearby materials. I set about finding a stick and carving that into a shaft that I could wiggle my blades onto. After a few false starts, I wound up with something pretty good. It was a foot shorter than ideal and had a worrisome flex to it which hinted it might snap when I needed it most, but worked pretty well. A blade plopping off the end was a constant worry, but we tried to tape them on and the stick fit pretty snuggly after I carved it down.

We set out on the river in late afternoon, knowing that paddling the river was committing to the trip because easy miles in the rafts would take days to reverse on foot.

Will is a stronger paddler than I, so he led the way and scouted the blind corners and log jams while I tried to make sure my blades stayed on my paddle. The paddling was mostly easy Class I-II floating but with a sportier section towards the end of those 22km (13 miles). Will ran some nice rapids, which I declined owing to them being near my upper limit combined with my improvised paddle and injured shoulder. I had badly dislocated the rafting the week prior in an incident really deserves its own post. In brief, I ran an ill advised un-scouted canyon after portaging several like it because it was too lazy to portage another and this one didn’t look as bad. I flipped on a complex 3′ drop and landed shoulder first on a boulder, which gave me my first dislocated shoulder of my life. I then spent a few minutes working it back into the socket, thereafter discovered my boat was stuck in a hole in the canyon, and then popped the boat to free it by tossing shale from the canyon rim after spending an hour exploring every other option. I capped the mishap by dislocating my now sloppy shoulder joint again while diving it to retrieve the freed boat. Back to this trip though, we finished paddling at sunset and dried our wet gear by a fire.

Day Three (8 Miles Hiking)

Our route from the Raush drainage to the Clearwater River totalled about 20 miles and looked to be some of the most spectacular terrain on the trip. It was filled with glaciers, moraines, and alpine valleys but also quite “forced” – as Will put it – because the terrain in the Caribou’s is serious stuff and finding any way through is hard. Instead of natural lines across gentle ridges and open bowls, the Caribou’s forced us towards passes that weren’t certain go, towards numerous cliff bands, across sidehills, and through generally tough slugging.

But the first half of this section was actually fairly good travel and one of the few portions I could actually recommend to someone. We ascended from the Raush River through thicker trees which meant less underbrush and reached the stunning alpine (+3000′) by late morning. It held a beautiful lake and behind that what we hoped was a pass.

Around this portion of the trip I realized I’d erred in the trip planning. Normally on challenging trips like this I’m solo, or at least the primary one responsible for executing the route. But here the route was mostly Will’s idea and knowing he was capable, I let my guard down and didn’t give the route the extreme scrutinization that I usually do. That’s not to say Will’s route was flawed – it was probably as good as it could be – but just that I personally didn’t have a rigorous grasp of what we were up against, which is an uncomfortable place to be when you’re facing terrain this serious. My lack of familiarity with the nuance of the route meant that I couldn’t fully contribute to decision making, and increased the intimidation. This may just be my personality as a bit of an obsessive control freak as the average person would have likely found my familiarity with the route quite robust. I like to know every contour line.

As an example of the above, I noticed for the first time that the upcoming pass had an awfully high concentration of contour lines on the back. Will said he was confident it would go, while my assessment after peering at the map was 50/50. I trusted Will but still wished I’d looked closer on Google Earth. After some anxiety, Will was proved correct and we were able to descend steep talus around cliff bands that were abundant but not that hard to avoid.

We spent the rest of the day traveling slowly through difficult but incredible alpine. We walked moraines, scrambled over ridges, hopped big talus and crossed icefields with cascading meltwater. All of it was serious terrain and quite a challenge but one that rewarded. Our route is shown below. We navigated the snowfields and glaciers on the left side to eventually reach the lowest point on the horizon (center of photo). It looks far but it’s about 4 miles.

We ended the day with our tent perched in a beautiful spot in the alpine. It was a great day, but still one that did little to alleviate worries about the overall magnitude of the trip. We’d worked all day to cover a mere 8 miles. We were far into the trip thanks to the fast miles on the Raush River, but on foot we’d only covered 19 of 55 miles, and those had taken us 3 days. This average of 6 miles per day was worrisome with 36 foot miles still ahead. We went to bed planning to rise early and aim for double digit miles.

Day Four (12 miles)

We were on the move at 6am and aiming for the Clearwater River twelve miles and perhaps a million hours away. The first half of the day involved contouring through several alpine bowls which looked like awfully steep sidehilling but was perhaps passable if we could stay above treeline.

Soon after we dipped too low and got caught sidehilling in near impenetrable rhododendron, boulders and alder. We re-aimed upwards, crested into the sub alpine and were able to resume progress. For the rest of the morning we able to maintain semi-reasonable progress through hard but stunning alpine with a respectable average speed near 1 mile per hour. The steep alpine slopes again presented numerous opportunities for wiping out, which we involuntarily obliged as we revived our game of “who can wipe out the fewest times” with me usually losing. In addition to my lost paddle shafts, the toll of wiping out mounted and I added a bruised shin, snapped trekking pole, torn rain pants and new ventilation in my jacket to the tally. Both feet were also coming pretty close to escaping out the sides of my torn La Sportiva’s, requiring me to step gingerly while sidehilling.

The alpine wasn’t all semi-reasonable terrain though. We approached what looked like a cliff band across the face we were traversing and suspected it was the crux of the day (it wasn’t). The cliff was indeed substantial: 50-100′ high and mostly low-mid 5th class choss. We scouted up and down, with me eventually finding a relief in the cliff band up a steep, chute that was half scrambling and half wet vegetation. It was easy enough to be dangerous, as upward progress wasn’t hard but a slip on the wet botany would result in a non-arrestable tumble to the talus below. I moved carefully trying not to dislodge rocks, but did send one down that gave Will a good reminder not to start upwards until I cleared the top.

Once surmounted, we followed a game trail through a weakness in a second cliff band and were able to resume progress towards to the Clearwater River on relatively good terrain. By mid-afternoon we had notched a healthy 8 miles, leaving a 3 mile descent along a ridge to the river, and then another mile down river to our put in. This was also the point where we had the option to turn uphill towards the unclimbed summit of Kink SE1, but we already knew that option wasn’t in play given our slow progress.

The descent started good enough, but with the brush growing steadily thicker (something I completely failed to take pictures of because thick brush hardly seems photogenic in the moment). By the last mile I was feeling defeated by the near impenetrable brush, even though I know it’s these slow times when continuing to push makes the biggest difference. Thankfully Will has spent his formative years in thick bush out east, and was able to lead with a strong cadence while I summoned the will to keep up. The last half mile was a brutal and near sub-botanical journey through an over-the-head mix of Devil’s club and slide alder. Notaby, it dealt a blow to Will when he strained his tibialis by catching it under a branch (tibialis: a muscle in the shin that opposes your calf and does the job of holding your foot up). I could tell it was bad because he started trying to use his gaiter to tie his foot up to his leg.

Near dinner, we arrived at the banks of the upper Clearwater River as perhaps the first humans to do so in the last century. Almost every party in the modern era that has done anything nearby has flown in to the alpine near their objective and been wise enough not to stray far from there, whereas we were deep in the valley bottom and largely trapped against the river by steep slopes on all sides.

A more immediate problem though was the swift tributary flowing in the west that we need to cross. Obviously unfordable, we discussed blowing up the rafts but I was hesitant given the waning daylight and time it takes to assemble and pack up the boats. We had notched a healthy 11 miles already, but still needed to complete 1 more before we reached our put in on the Clearwater River which held a potential gravel bar for camping (between here and there was almost entirely steep slopes to the river).

I looked closer at a Cottonwood fallen across this tributary and wondered where on the spectrum of “scary” to “stupid” would it be to cross on the tree. I suggested it to Will, who quickly declined, but I persisted knowing that the difference between a stupid move and genius one can be difficult to say without further exploration. Some moves can be both. I worked my out on the ever skinnier trunk but 80% of the way across a vertical branch impeded further progress. Normally you can use a branch like this as a nice handle and step around, but this one was so flexible that if you tried to pass on either side, the branch would just bend and tilt you towards the fast moving water.

I tried a few approaches to get past before mastering the “dipsy doodle” – an improvised move that involves crouching as low as possible to minimize leverage on the branch, and then hanging off the branch on the down river side (to avoid strainer risk) while it flexed enough to put your backside and pack just inches above water. The groan of the branch added just the right amount of spice to the move. Past the branch, the trunk narrowed further and flexed downward to a smooth dismount for those able to maintain balance for those narrowest 6 feet. Once across, I coaxed Will to give it a shot and minutes later he was across as well. In the moment and immediate aftermath he wasn’t impressed, but agreed later it was the right call. I was stoked.

We set off down river with a just mile to go until our put in spot and hopeful camp, which ended up being the longest mile of our entire trip. Progress was near impossible to come by due to thick vegetation on steep slopes. An hour later we had notched only a few hundred yards as we spent most of our time moving up and down the slope searching for a line forward between thickets and cliff bands. By two hours we had notched a half mile, which was very discouraging and eye opening. Prior to the Caribou’s I had always considered 1 mph to be “bad bushwacking” yet here we were clocking about 0.25 mph which is so much slower. An eight hour day at that pace would net a mere 2 miles. It changed my perspective of bushwacking.

One moment in particular stood out to me as the low point of the bushwacking. We had just descended to the rivers edge in hopes of a line below a cliff face, which wasn’t there. I was leading and gave a look back to Will who was dealing with a lot of pain from his injured foot. He said “I guess we gotta go back up” which was exactly what I didn’t want to do because the brutally steep and thick slope was why I tried descending to the rivers edge in the first place. Going up meant climbing up a wet slope so steep that you couldn’t ascend it if the vegetation weren’t there to hold. It was perhaps 60 degrees and with no obvious way of making any down river progress even if elevation was gained. But it was the only option so I began climbing up through the alder while trying a new technique of refusing to think about our rate of progress.

The terrain eased slightly after the first half mile and we were able to sometimes wade dowstream knee to waist deep in the rivers edge while holding onto the willows for security, rather than traversing the vegetated sidehill. Bit by bit we made progress and I became increasingly emotionally tied to the rivers edge for the lure of progress it sometimes delivered. Even when the rivers edge got perilous with boulders, I preferred to scramble them and considered it a win every time I covered another 10 or 20 yards downstream.

After 3 hours and about a mile, we were only a few hundred yards from camp and daylight was falling. I was keen to get there using the increasingly useful but still intermittently navigable rivers edge. Several times on the trip I had told Will how I’m “a sucker for the glory line” and these statements grew more frequent now as I pursued improbable scrambling lines around exposed boulders on the rivers edge rather than head back into the vegetation. Some worked, some didn’t. The lines grew increasingly bold and culminated at a rock face a mere 100 yards from camp where our path was blocked by a 20′ slab perched above boulders above the river. It looked impassible but as a sucker for the glory line I figured I’d check it out before admitting defeat and retreating into the alder. The wet 70 degree slab did have a few edges and seemingly a line to the top using side pulls and friction feet on slopers, so I focused on the moves rather the outcome of a fall (perhaps 20′ onto boulders and then tumbling into the raging river). The moves were solidly 5th class but trustworthy and soon I was at the top. Thereafter Will rounded the corner, looked up at the face, and entered a very dangerous situation: when you’re tired and faced with a choice between a quick but dangerous option (the climb), or a safe but exhausting one (bushwacking around). A very similar conundrum to what led to my dislocated shoulder the week prior.

I had been comfortable on the climb and knew with confidence I could execute it, but as Will started up the face I grew worried because I didn’t know what his experience on 5th class rock was, other than that he’s not a climber. I didn’t want to disturb Will mid-climb, but I was grew concerned that I had led someone into a bad spot. That feeling grew much worse when I saw Will gingerly testing a wet sloper of a foothold in the same manner my wife does when she’s considering trusting a terrible hold. Thankfully for Will he was able to climb through and we were soon at camp. He asked me later how hard I thought that face was and I put it at 5.7.

We ended day four clearing a tent pad out of avalanche deposited gravel alongside the Clearwater River, sitting around a fire and going bed just after dark. 12 miles on foot was a new record for the trip, but it came as a result of 16 hours of effort.

Day Five (11 miles paddling)

We awoke on day five to rain and concern from Will about the state of his foot. His tibialis injury from yesterday hadn’t miraculously cured overnight, as we had hoped but didn’t expect. For the first time, Will suggested that bailing might be the appropriate thing to do. More immediately, Will suggested taking the day off and seeing if the rest was any help. Sleeping in sounded pretty good to me after the ~16 hour effort of the day prior, but I really wanted to at least paddle the Clearwater since we were there and the weather was holding. We decided to sleep until lunch and then paddle.

The Clearwater river was flowing high and turbid from the recent rain and incredibly wet summer when we put in for the first recorded descent. At least I think it was. Will did most of the research for this trip and he’s pretty sure no one else has paddled it. I did a bit of Googling and found an ominously titled book called “Disaster on the Clearwater: An account of an attempted first descent of British Columbia’s Clearwater River“. However, that group had actually started about 80km downstream. The Clearwater River runs out of the alpine in Well Grey Provincial Park into Hobson Lake, then Clearwater Lake, until it joins the North Thompson River. That group was attempting to run the lowest section downstream of Clearwater Lake, while we were attempting to run the upper river from near its alpine source to Hobson Lake. We had entered the watershed near where the river leaves the icefield, and then paralleled the river in the alpine until the point where we deemed it runnable – 18 km (11 miles) upstream of Hobson Lake.

From here, Google Earth indicated numerous moderate rapids in the first 8 km plus a narrow canyon with what appeared to be a major waterfall. Will was in a much more conservative mental state than he was on the Raush due to the mental toll from his leg injury. He grew concerned about other rapids leading in to this canyon, while I was quite averse to further forays in the bush and pushed for paddling as close to the waterfall as we could, knowing that the difference between a 200 yard and 800 yard portage could be hours.

In the end, the river went well with us paddling most everything except the serious canyon. We didn’t get a good look at the feature it contained because it was hard to see from our portage but it sounded substantial but not enormous. Perhaps it was a beautiful clean drop, but there was no way to tell without bushwacking down to the canyon edge, and paddling it thereafter would have meant bushwacking 30 minutes back. Even it was a nice Class IV drop, I doubt either of us would have given it serious thought in our beat-down state. Will was obviously in a lot of physical and mental anguish from his foot injury, while I was just trying to keep forward progress happening with a banged up shin, and paddle shaft hewn from local alder. My wooden paddle shaft had worked well enough on the Raush despite being short and flexy, so I’d packed it through the alpine for use on the Clearwater as well even though it seemed likely to snap if I ever got into a bad spot and needed to paddle hard.

A second 1 mile canyon was also intimidating as it was potentially inescapable once entered, but Google Earth showed no sign of serious rapids. Still, canyon’s need to only have one problematic feature to be a bad idea as I found out the week prior. Will announced that we should portage it, but I was hesitant to undertake a brutal and potentially unnecessary portage, so I petitioned him to paddle from eddy to eddy as far in as we could, and only take out if the canyon was no longer escapable. In the end, it was a beautiful and intimidating section but free of serious obstacles. Soon we were through to the wider floodplain section that runs the last 10km to Hobson Lake.

Here we relaxed and enjoyed the rest of the float while marvelling at how high the water was. Virtually every tree on the floodplain was at water line – indicating this was about as high as the water got. I’ve hardly mentioned it here, but it rained much of the trip and has been the wettest summer in the past century in the area.

By early evening we arrived at the still waters of Hobson Lake. The remoteness of Hobson Lake is impressive considering that large lakes like this are normally lined with cottages. Here there is not even a footpath accessing this 30km long waterbody. After taking out, Will and I had a good talk about the trip; including what we’d learned, how it compared to expectations, how to decide when it’s appropriate to bail, and whether we should. The remaining portion was 42km (26 miles) through mostly alpine but with a few brutal stretches below treeline. The alternative was paddling 4km down Hobson Lake, bushwacking 5km to meet an old trail that may not exist, and then another 5km out the decrepit trail. That doesn’t sound too bad, but it spits us out at the opposite end of the 100km long Quesnel Lake as a small town (Likely, BC), and even arriving there still has us on the opposite site of the Caribou mountains from our car about 400km away. I told Will I could do the alpine section but was tired and sore and wouldn’t be upset if he wanted to bail. Him finding the justification to bail would be a relief for me, as I was beat and intimidated but without sufficient reason to call it off. In general, I’m wary of bailing if I don’t have a strong rationale for doing so, because I fear that might lead to a habit of bailing whenever the going gets tough.

At present I think I’m in a good mental state as it pertains to bailing on trips. I used to never bail on trips but really over did it a few times. In recent years I’ve gained maturity here and have bailed a few times when it was clearly the right call, while still never simply wimping out. I don’t want to get in the habit of wimping out because metal toughness is hard thing to gain and an easy thing to lose. If you let your fears make your decisions, you’ll never get anywhere near to what is possible.

Day Six (4 miles paddling, 6 miles on foot)

We awoke with no substantial improvement in the function of Will’s foot, so we made the decision to bail at Quesnel Lake. In the moment it was relieving decision to make, although I knew I’d be a bit regretful about it later, as I am. The southern alpine leg was the least “forced” portion of our trip and had some pretty epic ridges to walk, although certainly with much suffering as well. I gave a final look at the ridge which was to be the start of our alpine route, and started off paddling after Will on our bail route.

[Post script: Will used his InReach to text his mom, who arranged a boat pick up for us at the end of Quesnel Lake. We paddled for 2 hours, bushwacked for 3, hiked for 1, and then road the boat for another 4 hours. On day 2 of our bail we hitchhiked three times to Kamloops and then rented a car to drive to my car near Valemount and 48km up the North Thompson FSR . It’s unclear whether our 2 day bail was any quicker than completing the route but it was less effort. On hindsight it was the right call for Will. I wish I’d had the courage to take on the last leg solo because it was an option and likely a spectacular one. Forging on without a partner after everything we’d been through would have taken an immense amount of courage that I wish I’d had].

Brilliant report. Thanks for sharing.

That’s a serious trip! Well done

Great story, with a little bit of everything. I hope Will’s leg healed up quickly.

This was a wild trip and I’m really glad we did it despite the way it ended. You neglected to mention all the time you spent kicking our steps in the alpine, and the night I kicked over the cooking water 3 times in a row walking around the fire. Which I appreciate, but I think both should be preserved for posterity.

Great trip, enjoyed the read.

Excellent report; love the maps and photos. Will is one tough dude to keep going so far and so well with an injury like that. Hope you fellows didn’t use up too many of your “Avoid Early Arrival at the Pearly Gates” cards on this trip.

That’s not a trip I’d take on. But still, I wonder what all you took with you to, almost, have all you needed to get through. And what did you eat? I’ve never see those inflatables before either.

Living vicariously and thanking you for the ride.

+1 to Steve – I’d love to know what you brought on a trip like this. Particularly as your BMWO videos have given me the packrafting bug. 😉

Epic. Thanks for sharing. No wonder the Jackpine is NBD.

This is bananas. Well done!

Very well done report… thank you.

This is an epic adventure that you two had. It brought back memories of related trips of old (but much easier) where I had similar bail/not bail jitters, combined with a high degree of suffering.

Now that is an adventure! And all in a week. Fantastic, enjoyed reading that.